Case cross over studies

Among cohort designs, crossover studies are intervention studies in which the same group of people is exposed to two different interventions in two separate periods of time. This requires that the effect of the intervention is short enough not to impact the effect of the second intervention and that a time gap between the two interventions is respected. [1]

Case-crossover studies are the case-control version of crossover studies. This concept was introduced by Maclure et al. [2] [3]. In a case-crossover design, all subjects are cases, and exposure is measured in two different periods of time. The general principle is to find an answer to the question: “Was the case patient doing anything peculiar and unusual just before disease onset?” or “Did the patient do anything unusual compared to his routine?”. The assumption is that if there are triggering events, these events should occur more frequently immediately before disease onset than at any similar period distant from disease onset.

In case-crossover studies, instead of obtaining information from two groups (cases and controls), the exposure information is obtained from the same case group but during two different periods of time. In the first period, exposure is measured immediately before disease onset. In the second period, exposure is measured earlier (supposed to represent background exposure in the same person). Exposure among cases just before disease onset is compared to exposure among the same cases earlier. Therefore, each case and its matched control (himself) are automatically matched on many characteristics (age, sex, socio-economic status, etc.)

To illustrate that point, Maclure used the following example. Let's suppose we study the role of heavy physical activity in the occurrence of myocardial infarction (MI). Using a case-crossover design, we could document exposure to heavy physical activity among cases in the hour immediately preceding MI. We would then document exposure to heavy physical activity among those same cases at another earlier time.

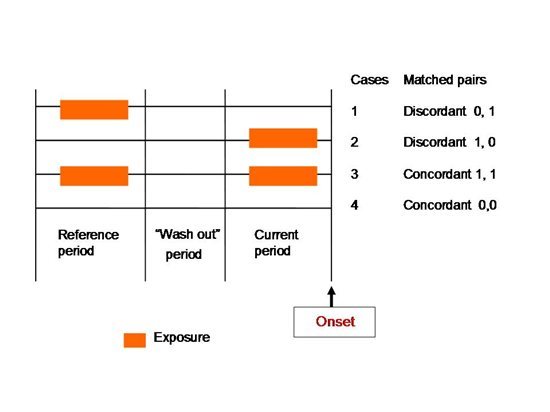

The following figure illustrates periods of exposure taken into account in a case-crossover study.

Source: Adapted from Jean Claude Desenclos, InVS, France

In the above figure, the period immediately before onset is called the «current» period, and the other period “the reference period”. The two periods are separated by a “washout period” to avoid that exposure in the reference period being mixed with exposure in the current period. The reference period of exposure reflects the average exposure experience among cases. Case 1 was unexposed in the current period (just before onset) and exposed in the reference period. Case 2 was exposed just before onset and unexposed in the reference period. Case 3 was exposed in both periods, and case 4 in none.

From the above, we should consider that the same case and its two periods of exposure constitute a matched pair. Cases 1 and 2 are discordant pairs, and cases 3 and 4 are concordant. This is why a matched pair analysis is required with a case-crossover design. Only discordant matched pairs will be used in the analysis (see chapter on matching for rationale).

In addition, some characteristics of exposure and outcome are noteworthy.

- Exposure should change over time in the same person and over a short period of time.

- Exposure should not change in a systematic way over time. In the example of physical activity, let's suppose we have documented exposure in the hour immediately before onset and that we have documented reference exposure two days before at the same time. This would not be appropriate if physical activity occurs in a systematic timing (every second day at the same time).

- Exposure should have a short-term effect. The duration of exposure effect should be shorter than the average time between two routine exposures in the same individual. The effect of a first exposure should have stopped before the next exposure.

- The induction time between exposure and outcome should be short.

- The disease must have an abrupt onset. A case-crossover design is inappropriate if the exact date/time of onset is unavailable or if abrupt onset does not exist (some chronic diseases).

- Several reference time periods can be used to document average exposure among cases. In that instance, an average of time being exposed is computed and compared to exposure just before disease onset. The efficiency of the case-crossover method increases with the number of reference periods included.

- As in any case-control study, the capacity to properly document exposure should be identical in the two periods of time. In case-crossover designs, information biases are a sensitive issue.

- Even if confounding is controlled since a case is under its own control, within-person confounding can occur. In the example of heavy physical activity and MI, another factor (anger) may be linked both to exposure (heavy physical activity) and outcome (MI).

Case-crossover and food-borne outbreaks.

Case-crossover design was sometimes used by epidemiologists to try to identify a food item as the vehicle for a food-borne disease outbreak. Several of the above-listed points merit being challenged. A recall (exposure) period of around three days may be too large to use this design. In addition, food habits (average exposure) do not happen randomly in an individual. Finally, comparing the consumption of a potentially infected food item in the “current” period to the average consumption of a similar un-infected food item in the reference period does not relate to the same exposure. Consumption of a food item could be identical in the current and reference time periods, and still, only the food item in the current period was contaminated.

References

- ↑ Rothman KJ. Epidemiology. An Introduction. New York, Oxford University Press 2002.

- ↑ Maclure MA, Maclure M, Robins MJ. The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. American Journal of Epidemiology 1991; 133(2):144-153

- ↑ Maclure, M, Mittleman MA. Should we use a case-crossover design? Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2000; 21:193-221

FEM PAGE CONTRIBUTORS 2007

- Editor

- Masja Straetemans

- Original Authors

- Alain Moren

- Jean Claude Desenclos

- Marta Valenciano

- Arnold Bosman

- Contributors

- Arnold Bosman

- Lisa Lazareck

- Masja Straetemans

Root > Assessing the burden of disease and risk assessment > Field Epidemiology > Methods in Field Epidemiology > Types of Study > Non-traditional designs